Chronic Inflammation (Part 1): causes, belly fat, lab tests, and more

What is inflammation, how does belly fat impact inflammation, how is inflammation measured, and how inflammation affects vitamin and mineral levels.

Hey,

Before we talk inflammation, I paused billing on my Substack for the last month or so. I haven’t written as regularly as I hoped. I just resumed billing so anyone being invoiced monthly, just a heads up, and I want to again thank you for your support; it allows me to make researching and writing part of my work. Thank you.

Ok, onto today’s topic…

Inflammation

Would it surprise you to hear that inflammation isn’t all bad? If we didn’t have inflammation, even a paper cut would kill us. This is all thanks to our amazing immune systems that are set in motion from the inflammatory triggers I’ll explain below.

I used to show this Time cover in presentations I gave about inflammation. Before you look at the date on the top left corner, guess what year this was published…

Can you believe it was published exactly 20 years ago? Inflammation has gained even more popularity and attention with social media and also as more people try to fight inflammation in their day-to-day lives, whether it’s taking ibuprofen, being on a round of steroids, or following an “anti-inflammatory diet.” However, not all inflammation is bad.

In fact, inflammation is lifesaving.

Today’s newsletter is the first in a 2-part series on chronic inflammation. In this newsletter, I’ll explain: 1) what inflammation is and why we have it, 2) the two main types of inflammation, 3) what causes inflammation, and 4) lab tests that measure inflammation. In the next newsletter, I’ll discuss diet and nutritional connections to inflammation and lifestyle strategies to lower chronic inflammation.

What is inflammation?

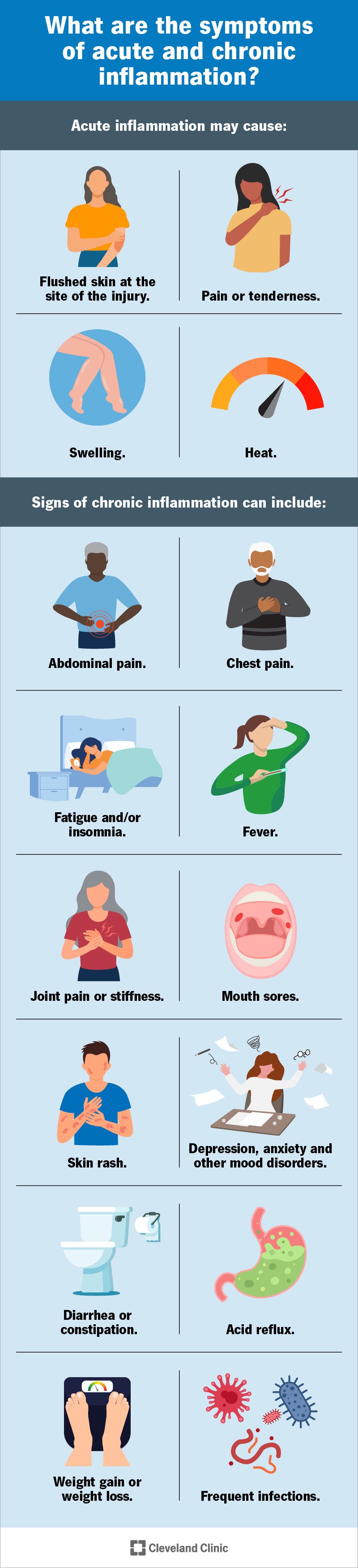

Inflammation is a process our immune system initiates after being triggered by: 1) tissue damage (e.g., a cut, burn, or even dying cells), 2) infections (e.g., bacteria like strep throat or e. coli; or a virus like COVID or a cold), or 3) toxicants (e.g., mold, heavy metals, asbestos, or bisphenol A (BPA)). Inflammation causes redness, heat, pain, swelling, and/or loss of function. There are different types of inflammation, but the primary two types of inflammation are acute and chronic inflammation. I will explain each, but the main focus of this series is chronic inflammation.

Types of Inflammation

Acute inflammation

We can be grateful for short-term, acute inflammation because it triggers the body to heal. Examples of acute inflammation are: getting a cut, burn, or an injury like a bruise or a bone break. Infections like a cold or the flu can also cause acute inflammation. The main thing to remember about acute inflammation is that it ultimately leads to healing; it’s net-beneficial.

Chronic Inflammation

On the flip side, chronic inflammation can lead to further tissue damage. Persistent inflammation leaves the immune system nearly constantly at work, which causes inflammation to persist (instead of resolving once the trigger clears). Chronic inflammation can last months to years. I describe the signs and symptoms of chronic inflammation below, but generally chronic inflammation can be less obvious than acute inflammation as it can sneak in slowly over time.

Inflammaging is a newer concept that describes the chronic inflammation of aging. Inflammaging is a low-level, chronic inflammation that leads to elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers like C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha, which I’ll explain more below. The deterioration of the immune system that comes with aging—“immunosenescence”—is thought to cause inflammaging. (1)

Why is Chronic Inflammation Such a Big a Problem?

Chronic inflammation isn’t just problematic because it causes pain, fatigue, mood changes, or poor sleep. Chronic inflammation is harmful because it increases risk for metabolic risk factors like high blood pressure, dyslipidemia (high levels of “bad” cholesterol and low levels of “good” cholesterol), insulin resistance, fatty liver and it increases the risk for diseases like cancer, depression, autoimmune conditions, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic conditions. (2) Diet is one of the many factors that contribute to increased risk for developing and sustaining chronic inflammation, which is why I’m talking it.

Body Composition (Muscle vs. Fat) and Chronic Inflammation

Concern around inflammation and body weight is more specific to body composition (the proportion of body weight that’s fat versus muscle and bone), especially around the midsection (belly fat). Belly fat—or to scientists, “visceral adiposity”—contributes to chronic inflammation. As fat grows and expands, the body can’t keep up, and this new tissue isn’t sufficiently vascularized (can’t get enough nutrients), resulting in tissue damage that triggers inflammation. This inflammation is the body’s effort to heal the damaged tissue (see acute inflammation, above). I love this example of our bodies trying to take care of us even when the net effect is harmful. Our bodies are doing the best they can to fix a problem (trying to get blood supply and nutrients to new tissue).

Other Causes of Chronic Inflammation

While belly fat is a prevalent inflammatory trigger in the US, other factors drive chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation is also caused by endocrine disrupting chemicals (like bisphenol A or “BPA” and many others) (3), stress (4), diet (5), sleep (6), movement (7), and other factors. (8, 9) Since there are so many contributing factors to chronic inflammation, it’s hard to say that any one specific factor is the most important because they all contribute to someone’s overall inflammatory load.

Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Inflammation

In a 2019 review published in Nature (2), the authors describe “sickness behaviors” that characterize signs of chronic inflammation: sadness, inability to feel pleasure, fatigue, low sex drive, low food intake, too much or too little sleep, social isolation or withdrawal, and biometric changes like elevated blood pressure, blood sugar dysregulation and unhealthy cholesterol levels. (2) The start of this list may sound like symptoms of depression, which is interesting because people with depression are 50% more likely to have elevated inflammation compared to people without depression. (10) These signs and symptoms are different than those of acute inflammation. Since these “sickness behaviors” can be attributed other causes, linking these directly to chronic inflammation can be tricky. However, it can illustrate the subtlety of chronic inflammation as compared with acute.

Belly Fat and Chronic Inflammation

Visceral or “belly” fat can actually be a physical sign of chronic inflammation. (11) In part it likely indicates inflammation because of what I described above (inflammation results from inability to vascularize new and growing fat tissue). You can measure body composition using bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA), Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA), or even magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A simpler way to measure belly fat is to use a flexible (“sewing”) tape measure and measure the circumference of your waist at the height of your belly button and held parallel to the ground. If you try this, use a mirror and try not to include any clothing in the measurement. An even easier way to track belly fat is to notice how your pants are fitting at a consistent position around your waist.

Blood Tests for Inflammation

There isn’t one single test or standard lab panel for chronic inflammation (2), but here is a list of some of the lab tests that can show chronic inflammation in the body. I put the more common tests (that your doctor might use) toward the top and the less common (that researchers might use) at the bottom:

High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP): cardiovascular risk marker and also a general indicator of chronic, low-grade inflammation.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR or “sed rate”): elevated in some people with autoimmune diseases.

Ferritin: also a marker for iron status and storage but ferritin doubles as a marker of inflammation when elevated and other iron markers suggest normal iron status.

White blood cells (WBCs): when elevated, WBCs may indicate inflammation due to immune system activation.

Fibrinogen: inflammation related to cardiovascular disease.

Interleukins (ILs) IL-6, IL-1β, IL-18: elevated with chronic inflammation.

Leukotrienes and prostaglandins: made from arachidonic acid, which is in high amounts in a Western diet and allow the production of these inflammatory molecules.

Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB): can be elevated with infection and a marker of chronic inflammation.

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α): elevated in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Micronutrient (vitamin/mineral) Levels and Inflammation

One important consideration for people with chronic inflammation is the impact it can have on assessing someone’s nutritional status. (12) Certain vitamin and mineral levels can be affected by inflammation. Specifically: iron levels (via the blood test, ferritin) can be falsely elevated in the presence of inflammation (as listed above). Alternately, inflammation can falsely suppress levels of vitamin A and zinc. These are important considerations when testing vitamin and mineral levels if someone’s levels are out of the “normal” range without nutrient malabsorption or excessive supplementation. Someone may appear to have low levels of vitamin A or zinc but, in fact, are experiencing chronic inflammation.

Diet and Chronic Inflammation… To be Continued

My next installment of this series will dig into specifics of chronic inflammation related to diet. Let me know if you have any specific questions about this you would like me to include in the newsletter!

References

Pan W. Aging and the immune system. Molecular, Cellular, and Metabolic Fundamentals of Human Aging. 2022 Oct 23:199.

Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, Ferrucci L, Gilroy DW, Fasano A, Miller GW, Miller AH. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature medicine. 2019 Dec;25(12):1822-32.

Bergman Å, Heindel JJ, Jobling S, Kidd K, Zoeller TR, World Health Organization. State of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals 2012. World Health Organization; 2013.

Ravi M, Miller AH, Michopoulos V. The immunology of stress and the impact of inflammation on the brain and behaviour. BJPsych advances. 2021 May;27(3):158-65.

Margină D, Ungurianu A, Purdel C, Tsoukalas D, Sarandi E, Thanasoula M, Tekos F, Mesnage R, Kouretas D, Tsatsakis A. Chronic inflammation in the context of everyday life: dietary changes as mitigating factors. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020 Jun;17(11):4135.

Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE. Sleep disturbance, sleep duration, and inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies and experimental sleep deprivation. Biological psychiatry. 2016 Jul 1;80(1):40-52.

Khalafi M, Malandish A, Rosenkranz SK. The impact of exercise training on inflammatory markers in postmenopausal women: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Experimental Gerontology. 2021 Jul 15;150:111398.

Nivukoski U, Niemelä M, Bloigu A, Bloigu R, Aalto M, Laatikainen T, Niemelä O. Impacts of unfavourable lifestyle factors on biomarkers of liver function, inflammation and lipid status. PLoS One. 2019 Jun 20;14(6):e0218463.

Muscatell KA, Brosso SN, Humphreys KL. Socioeconomic status and inflammation: a meta-analysis. Molecular psychiatry. 2020 Sep;25(9):2189-99.

Osimo EF, Baxter LJ, Lewis G, Jones PB, Khandaker GM. Prevalence of low-grade inflammation in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of CRP levels. Psychological medicine. 2019 Sep;49(12):1958-70.

Bawadi H, Katkhouda R, Tayyem R, Kerkadi A, Bou Raad S, Subih H. Abdominal Fat Is Directly Associated With Inflammation In Persons With Type-2 Diabetes Regardless Of Glycemic Control - A Jordanian Study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019 Nov 22;12:2411-2417. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S214426. PMID: 31819567; PMCID: PMC6878926.

Ghosh S, Kurpad AV, Sachdev HS, Thomas T. Inflammation correction in micronutrient deficiency with censored inflammatory biomarkers. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2021 Jan 1;113(1):47-54.